This is a short essay on the research and process behind my project Fly Over My City which I wrote for the University of the Arts London’s graduate showcase.

At the beginning of a project I tend to start scoping far and wide before later moving inwards to the more personal and local. I jot down a broad set of ideas of subjects or themes that interest me and then ask: What links these? What personal reasons do I have for being drawn to these things? This helps me get clearer over time on what I want my work to say. I then wander about a bit and read newspapers, go to the cinema and watch films on unrelated topics, quiz friends, browse the internet, read books and look at paintings. I don’t look at photography very much really. I collect ideas as I go. Sooner or later it becomes clear to me which specific story or subject I want to focus on. I then do three things: I look at how the subject has already been represented by others, I get as close as possible to my subject, and I speak to the people who know most about it.

For Fly Over My City, I interviewed a range of people playing critical roles in raising community awareness of nature and, more specifically, swift conservation in London to understand not only the ecological story but the human story – the drivers behind people’s attachment to these birds. Some of these conversations were deeply emotive and poignant. Each interviewee then linked me to another interesting person and so on. This helped give me a better understanding of the system and context within which I was operating.

Swifts spend most of their lives on the wing, so outside the summer time the only way to see them in real life is to view dead specimens. The first place I thought of to do this was the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, where I used to volunteer as a biology student. The museum allows the public to use their collections for research purposes. I made sketches of the swift skins to get familiar with their features (I find sketching is more useful for this than taking photographs). This allowed me to bring in a sense of materiality to my project and to reflect on affinities between observed natural and human-made aspects of the subject and its context, e.g. feathers are soot-coloured like the city, and charcoal; weightless swift bodies mirror the human imagination etc.

Working in the collections also inspired me to bring a museological feel to the final exhibition design and this in turn allowed me to find a way to bring myself into the process. By incorporating sound, touchable objects, writing, sketching and photographs, I reflected the sensory experiences I’d had when researching the project.

Later on, I went back to my original questions and the array of resources and seemingly unrelated snippets I’d come across at the scoping stage. I wrote about my own difficult experiences with living in the capital during the building safety crisis and this helped guide my image-making and make the work more personal. I reflected the diversity of communities in my local area as well as my and my contributors’ own heritage in the ‘imagined’ objects and details within the nest box, including Aso Oke fabric, Maggi cube packet, and cyanotypes toned with jasmine Chinese tea.

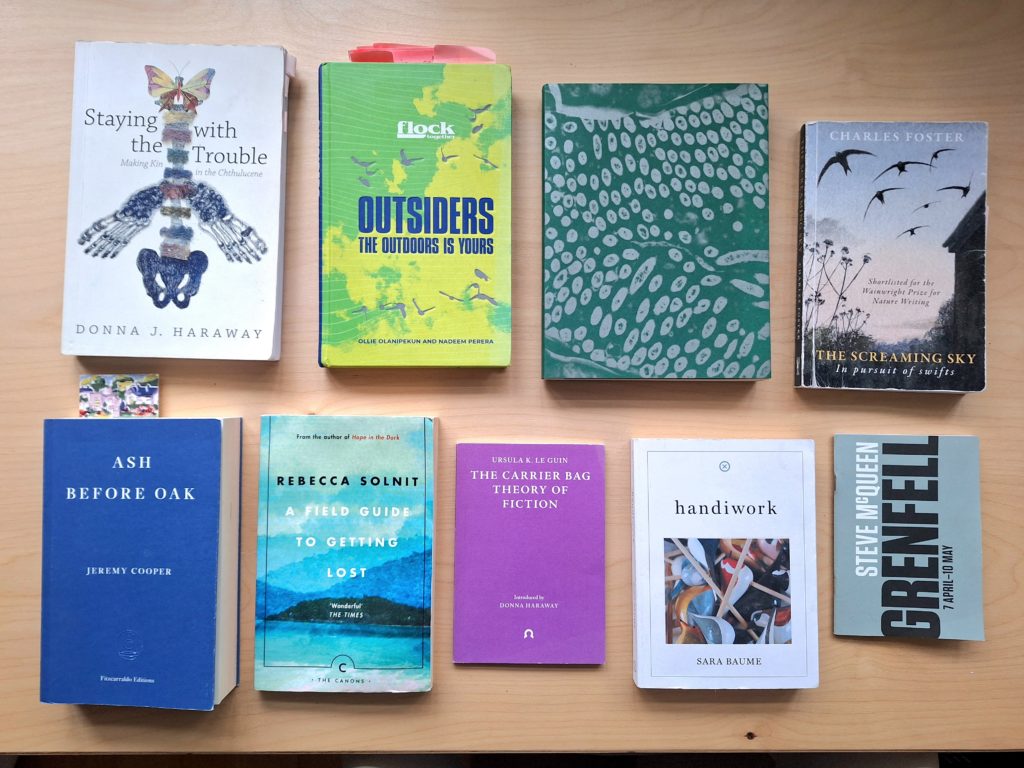

For inspiration on style and tone, the world of literature was particularly helpful in this development stage for ideas on narrative structure. I looked at nature-writing and books that adopted a fragmentary or sort of collector’s approach to weaving stories and which recognised the interconnectedness of things while leaving breathing room for gaps in knowledge and questions.

I had to wait until very late on in the project before seeing and photographing live swifts. I wanted to represent them in a way that was not recognisably nature documentary in style. I like to think that the indistinct, abstract shapes that resulted remind us that life keeps moving in its own nonconforming, undefinable way.

A selection of references used for Fly Over My City